The Auditorium of Grief

Each grief has a voice. Sometimes they speak at once. Sometimes they’re quiet, just sitting there with you. And for a while, you just let them.

Grief is a strange emotion. For most of my childhood, I was lucky — I didn’t experience much personal loss. Death was something that happened on television or in stories my parents told about distant relatives I barely knew, people I didn’t have memories of or context to care about. My ADHD probably played a role too — even when something did matter in the moment, it didn’t always stick long enough to feel real later.

That changed after I turned 19, when my grandmother from Texas died. It was my first real loss. Then, at 23, it all hit at once: in the span of a few months, I lost a close friend with muscular dystrophy, my other grandmother, and my husband’s grandmother. It was a season of loss so compact, so relentless, that I didn’t fully process what had happened. I didn’t know it then, but that was when the auditorium of grief quietly came into existence.

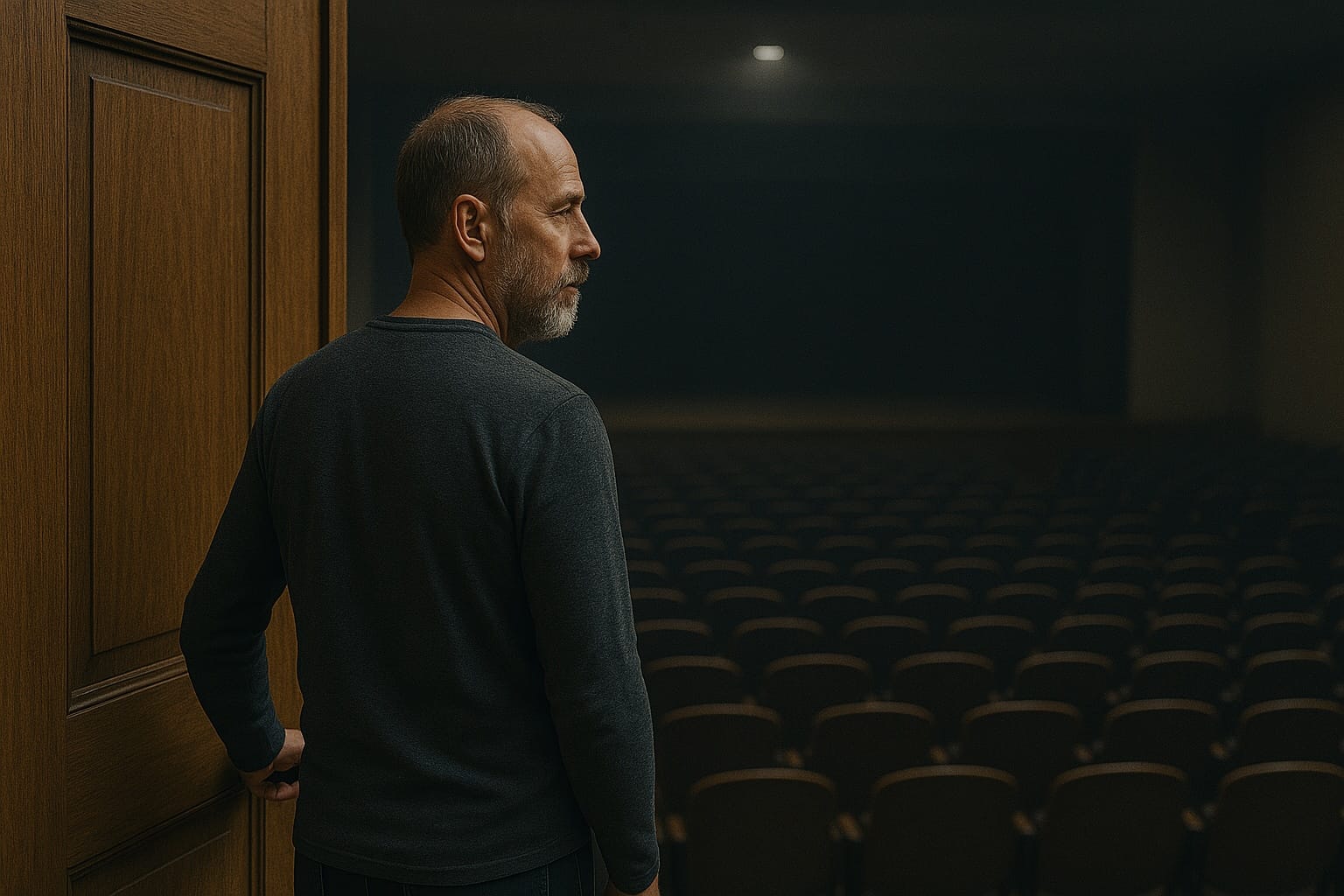

It sat there, dimly lit — not on any map I could identify, but undeniably real. Some seats were already occupied by those losses, each one settled in with its own particular weight. And there were many more seats, still empty, quietly waiting.

The Click of the Lock

Burkley was our first dog — my husband and I got him early in our relationship, and he became a constant in our lives for nearly 18 years. He wasn’t just a pet; he was a fixture in the background of everyday life. For the last five years of his life, I worked from home, so we were together nearly 24 hours a day. He was always there: curled up nearby while I worked, trotting behind me from room to room, waiting at the door when I came back from errands. A significant portion of my thoughts were dedicated to his presence.

Losing him was staggering, although not entirely unexpected. We made the decision to end his life because he was suffering, and even though it was the right choice, it didn’t soften the blow. In the days and weeks that followed, I found myself crying during completely ordinary moments, like while out on a run, watching TV, or taking a shower. Evenings were worse. The grief would hit suddenly, overwhelming me without warning.

But what I noticed was that I wasn’t only grieving Burkley. His death had clicked something open — that hidden door — and through it came the sorrow of every other loss I’d ever carried. It wasn’t just one goodbye anymore. It was all of them.

The Door Opens

There’s a strange thing that happens when deep grief takes hold — it rarely stays contained. You think you’re mourning one thing, one being, one loss, one moment. But then the weight of it shifts, and suddenly you’re feeling everything you never fully processed. Every sorrow seems to wake up at once.

That’s what it felt like after Burkley died. It started with his absence — his empty bed, the hollow sound of the fluorescent light buzzing in the quiet kitchen in the morning without sounds of Burkley — but what came next was harder to name. I wasn’t missing only him. I was missing my friend who died years prior. I was missing my grandmothers. I was missing people I hadn’t consciously grieved in years. The door to the auditorium had swung open again, and the crowd inside stirred.

Grief is recursive like that. It loops. It layers. One loss hands off the microphone to another. Sometimes you’re not even sure who’s speaking through your tears — you just know you’ve been pulled in.

Inside the Auditorium

When the door opens, you don’t so much walk in as fall in.

The space is quiet like a held breath, heavy with expectation, like in a theater waiting for something to begin. The lighting is low, but soft enough to make out rows of seats stretching far beyond what you thought your heart could contain.

Some seats are clearly occupied. You recognize them immediately — the big griefs, the ones you’ve sat with before. They hold your gaze without apology, making you feel uncomfortable. Other seats are hazier with the losses you forgot you knew. Things like an old friend you drifted from before they passed, someone you didn’t know well but still feel the absence of, the pets, the relationships with the living that ended because you moved, or changed jobs, or quietly outgrew each other.

Then there are the empty seats. Those are the ones that stop you cold. You know they’re not empty forever and what will occupy them could be harder than what's with you right now.

You sit among them all. You don’t really have a choice. The room holds you — in that strange tension of being surrounded by grief and yet somehow not alone. You realize you’re not there with the people and pets you’ve lost — you’re there with every past version of yourself who’s grieved before. The nineteen-year-old who didn’t know what to do with his sadness, the twenty-three-year-old who was overwhelmed by too much loss too quickly, the you from just last week who didn’t expect to cry so hard on the hiking trail.

Each grief has a voice. Sometimes they speak at once. Sometimes they’re quiet, just sitting there with you. And for a while, you just let them.

Exiting the Auditorium

You don’t know when or how it happens, exactly. The grief doesn’t end — it just quiets. The room doesn’t empty — it just recedes. And eventually, you realize you’ve stood up. You’re back at the door.

You might have only been in there for a short while, or maybe it’s been a few days. Either way, while you’re relieved to be out, there’s a strange part of you that misses it — the consistency of emotional experience, the clarity of feeling. Brains are weird like that.

Intermission

Grief has had a way of reshaping me — not all at once, but over time, visit by visit. It’s rarely just about what I’ve lost most recently. Each new grief brushes up against the old ones, stirring memories, emotions, and versions of myself I thought I’d outgrown or left behind.

The auditorium never really closes. It’s part of me — a quiet, heavy space that fills slowly over time. Sometimes I stumble into it unexpectedly. Sometimes I choose to walk through the door. And sometimes I just stand outside, hand on the knob, not quite ready. It wasn’t until my dad died in 2020 that I finally saw the auditorium clearly — and gave it a name. It had always been there. I just hadn’t noticed it completely.

But if you find yourself inside your own auditorium, know this: you’re not alone. Not in that room, not in this life, not in your grief. They may feel overwhelming but remember it is made up of love. Every seat is proof that you’ve lived, connected, and cared. Intermission will come and you will get through this.

“The deeper that sorrow carves into your being, the more joy you can contain.”

— From On Joy and Sorrow by Kahlil Gibran